[for a brief explanation of this ongoing series, as well as a full table of contents, go here]

[for a brief explanation of this ongoing series, as well as a full table of contents, go here]

“To be is to be the value of a variable.”

(Willard Van Orman Quine)

We have seen so far that philosophy broadly construed has a significant public relation problem, and I’ve argued that one of the root causes of this problem is its sometimes antagonistic relationship with science, mostly, but not only, fueled by some high prominent scientists who locked horns with equally prominent anti-scientistic philosophers. In this chapter we will examine the other side of the same coin: the embracing by a number of philosophers of a more positive relationship with science, to the point of either grounding philosophical work exclusively in a science-based naturalistic view of the world, or even of attempting to erase any significant differences between philosophy and science. This complex discourse is sometimes referred to as the “naturalistic turn” in modern analytic philosophy, it arguably began with the criticism of positivism led by Willard Van Orman Quine and others in the middle part of the 20th century, and it is still shaping a significant portion of the debate in metaphilosophy, the subfield of inquiry that reflects critically on the nature of philosophy itself (Joll 2010).

Two very large caveats first. To begin with, which philosophy am I talking about now? We have seen earlier that the term applies to a highly heterogeneous set of traditions, spanning different geographical areas, cultures, and time periods. To be clear — and for the reasons I highlighted in the last chapter — from now on and for the rest of the book I will employ the term “philosophy” to indicate the broadest possible conception of the sort of activity began and named by the pre-Socratics in ancient Greece, what I termed the DRA (discursive rationality and argumentation) approach. This will comprise, of course, all of the current analytic tradition, but also parts of continental philosophy, and certain aspects or traditions of “Eastern” philosophies. It will also include the work of modern and contemporary philosophers that do not fit easily within the fairly strict confines of proper analytic philosophy: both versions of Wittgenstein, for instance, at least some strains of feminist philosophy, and much more. If this sounds insufficiently precise that is — I think — a reflection of the complexity and richness of philosophical thought, not necessarily a shortcoming of my own concept of it.

Secondly, it must be admitted that venturing into a discussion of “naturalism” is perilous, for the simple reason that there is an almost endless variety of positions within that very broad umbrella, and plenty of people who feel very strongly about them. In the following, however, I will focus specifically on approaches to naturalism (and the philosophers who pursue them) that are most useful or otherwise enlightening for the general project of this book, which largely involves the relationships between science and philosophy and how they both make progress, albeit according to different conceptions of progress.

Basic metaphilosophy

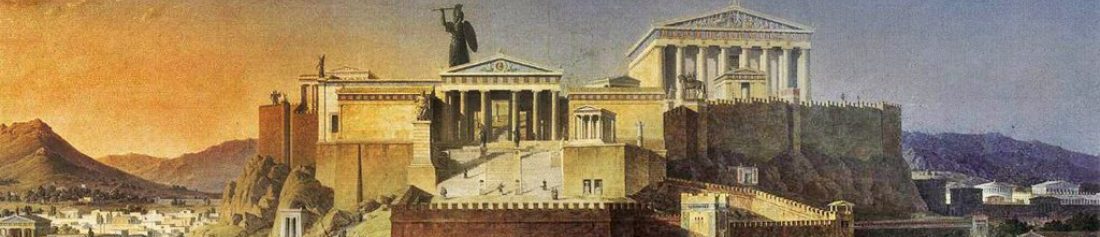

Before tackling naturalism, we need to indulge in a bit more of what is referred to as “metaphilosophy,” i.e., philosophizing about the nature of philosophy itself. We have already examined what a number of contemporary philosophers think philosophy is, and I argued that there is significantly more agreement than a superficial look would lead one to believe, certainly more than the oft-made comment that every philosopher has a (radically) different idea of what the field is about. Arguably the most famous characterizations of philosophy were those given by two of the major figures in the field during the 20th century, Alfred Whitehead and Bertrand Russell. Whitehead quipped that all (Western) philosophy is a footnote to Plato, meaning that Plato identified all the major areas of philosophical investigation; a bit more believably, Russell commented that philosophy is the sort of inquiry that can be pursued by using the methods first deployed by Plato. The fact is, discussions concerning what the proper domain and methods of philosophy are (i.e., discussions in metaphilosophy, regardless of whether explicitly conducted in a self-conscious metaphilosophical setting) have been going on since at least Socrates. Just recall his famous analogy between his trade and the role of a midwife, which conjures an image of the philosopher as a facilitator of sound thinking; or Plato’s relentless attacks against the Sophists, who thought of themselves as legitimate philosophers, but were accused of doing something much closer to what we would consider lawyering.

I think it is obvious that Whitehead was exaggerating about all philosophy being a footnote to Plato, regardless of how generous we are inclined to be toward the Greek thinker. Not only there are huge swaths of modern philosophy (most of the contemporary “philosophies of,” to which we will return in the last chapter) which were obviously inaccessible to Plato, but he (and especially Socrates) made it pretty clear that they had relatively little interest in natural philosophy, with their focus being largely on ethics, metaphysics, epistemology (to a point), and aesthetics. It was Aristotle that further broadened the field with the development of formal logic, as well as a renewed emphasis on the sort of natural philosophy that had already took off with the pre-Socratics (particularly the atomists) and that eventually became science.

A rapid survey of post-Greek philosophy shows that different philosophers have held somewhat different views of the value of their discipline (Joll 2010). Hume, for instance, wrote that “One considerable advantage that arises from Philosophy, consists in the sovereign antidote which it affords to superstition and false religion” (Of Suicide, in Hume 1748), thus echoing the ancient Epicurean quest for freeing humanity from the fears generated by religious superstition. This somewhat practical take on the value of philosophy was also evident — in very different fashions — in Hegel, who thought that philosophy is a way to help people feel at home in the world, and in Marx, who famously quipped that the point is not to interpret the world, but to change it.

With the onset of the 20th century we have the maturing of modern academic philosophy, and the development of more narrow conceptions of the nature of the discipline. The early Wittgenstein of the Tractatus thought that philosophy is essentially a logical analysis of formal language (Wittgenstein 1921), which was naturally well received by the logical positivists that were dominant just before the naturalistic turn with which we shall shortly concern ourselves. Members of the Vienna Circle went so far as promulgating a manifesto in which they explicitly reduced philosophy to logical analysis: “The task of philosophical work lies in … clarification of problems and assertions, not in the propounding of special ‘philosophical’ pronouncements. The method of this clarification is that of logical analysis” (Neurath et al. 1973 / 1996). From these bases, it was but a small step to the forceful attack on traditional metaphysics mounted by the positivists. Metaphysics was cast aside as a pseudo-discipline, and prominent continental philosophers — especially Heidegger — were dismissed as obfuscatory cranks.

I think it is fair to say that a major change in the attitude of practicing philosophers toward philosophy coincided with the diverging rejections of positivism that are perhaps best embodied by (the later) Wittgenstein and by Quine. We will examine Quine in some more detail in the next section, since he was pivotal to the naturalistic turn. The Wittgenstein of the Investigations shifted from considering an ideal logical language to exploring the structure — and consequences for philosophy — of natural language. As a result of this shift, Wittgenstein began to think that philosophical problems need to be dissolved rather than solved, since they are rooted in linguistic misinterpretations (cfr. his famous quip about letting the fly out of the fly bottle, Investigations 309), which led to his legendary confrontation with Karl Popper, who very much believed in the existence and even solvability of philosophical questions, especially in ethics (Edmonds and Eidinow 2001).

Most crucially as far as we are concerned here, the Wittgenstein of the Investigations was critical of some philosophers’ envy of science. He thought that seeking truths only and exclusively in science amounts to a greatly diminished understanding of the world. In this Wittgenstein clearly departed not just from the attitude of the Vienna Circle and the positivists in general, but also from his mentor, the quintessentially analytic philosopher Bertrand Russell. It is because of this shift between the early and late Wittgenstein that — somewhat ironically — both analytic and continental traditions can rightfully claim him as a major exponent of their approach. [1]

This very brief metaphilosophical survey cannot do without a quick look at the American pragmatists, who developed a significantly different outlook on what philosophy is and how it works. Recall, to begin with, their famous maxim, as articulated by Peirce (1931-58, 5, 402): “Consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.” Peirce and James famously interpreted the maxim differently, the first one referring it to meaning, the latter (more controversially) to truth. Regardless, for my purposes here the pragmatists can be understood as being friendly to naturalism and science, and indeed as imposing strict limits on what counts as sound philosophy, albeit in a very different way from the positivists.

I find it even more interesting, therefore, that the most prominent — and controversial — of the “neo-pragmatists,” Richard Rorty, attempted to move pragmatism into territory that is so antithetic to science that Rorty is nowadays often counted among “continental” and even postmodern philosophers. His insistence on a rather extreme form of coherentism, wherein justification of beliefs is relativized to an individual’s understanding of the world, (Rorty

1980), eventually brought him close to the anti-science faction in the so-called “science wars” of the 1990s and beyond (see the chapter on Philosophy Itself). He even suggested “putting politics first and tailoring a philosophy to suit” (Rorty 1991, 178). But that is not the direction I am taking here. Instead, we need to sketch the contribution of arguably the major pro-naturalistic philosopher of the 20th century, Quine, to lay the basis for a broader discussion in the latter part of this chapter of what naturalism is and what it may mean to philosophy.

Notes

[1] The discontinuity between the early and late Wittgenstein, however, should not be overplayed. As several commentators have pointed out, for instance, both the Tractatus and the Investigations are very much concerned with the idea that a primary task of philosophy is the critique of language.

References

Edmonds, D. and Eidinow, J. (2001) Wittgenstein’s Poker: The Story of a Ten-Minute Argument Between Two Great Philosophers. Ecco.

Hume, D. (1748) An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (accessed on 8 February 2013).

Joll, N. (2010) Contemporary metaphilosophy. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (accessed on 26 June 2012).

Neurath, O., Carnap, R., Hahn, H. (1973 / 1996) The Scientific Conception of the World: the Vienna Circle, in S. Sarkar (ed.) The Emergence of Logical Empiricism: from 1900 to the Vienna Circle. Garland Publishing, pp. 321–340.

Peirce, C.S. (1931–58) The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss and A. Burks (eds). Harvard University Press.

Rorty, R. (1980) Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Blackwell.

Rorty, R. (1991) The Priority of Democracy to Philosophy. In: Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth. Philosophical Papers, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1921) Tractatus Logicus-Philosophicus (accessed on 8 February 2013).

?doch nicht falsch

LikeLike

@Massimo

My apologies in bringing up the supernatural but it is what Naturalism aligns itself against. Here is a website on Naturalism:

http://www.naturalism.org/

This then of course leads to atheism.

This also leads to no mind/brain dualism or the “soul fallacy”

This also leads to no “first cause to the universe”

Here is a debate between Sean Caroll and William Lane Craig

This debate series continued with others like Tim Maudlin and Alex Rosenberg:

http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2014/04/15/talks-on-god-and-cosmology/

So i do not see how this cannot eventually come up when talking about naturalism since it is the philosophical view that best accounts for the findings of science. You even said it takes data into account as opposed to dreaming up stuff in an armchair or bar stool.

LikeLike

Brodix,

“Are we totally sure we are not crossing into a more modern form of “super” naturalism?”

Yes, I’m absolutely positive, please stop rationalizing things and stick to the OP, I’m getting a bit tired of irrelevant comments, and I will use my prerogative to ban people temporarily or permanently from the blog.

Mark,

Same idea, debates with Craig have absolutely nothing to do with what we a discussing here. C’mon people, focus!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Massimo,

Maybe my terms are off putting, but I did think the issue of MUH would fall along the line of what is natural and what is not. ?

LikeLike

Brodix,

I simply think you are engaging in far too much rationalizing regarding what is relevant to the OP. Please, try harder. Much harder. Thanks.

LikeLike

You know, on the last post and this both, missing from the “continental” side entirely is any mention, let alone discussion, of phenomenology? Is Husserl that dead as a doorknob in the philosophical world today, Massimo? As I was winding up my graduate divinity work, he, along with the young Wittgenstein, the logical positivists and Hume, were probably the most major helps in my transition to secularism.

I wound up eventually disagreeing with a lot of his ideas, but he did lead a former conservative Lutheran into some of 20th century continental thought.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Haulianlal,

This is only true if you yet again conflate the question regarding the working of science as it’s done by successful practitioners with the question of epistemological/ontological underpinnings of the enterprise of science. These are two separate issues and for the former question, it is certainly better to ask the practicing and successful scientists in the field than the philosopher of.

This of course only broadly true, there are people like Massimo who are in the middle and some philosophers of science may also have a PhD. in the relevant area of science so they may be able to speak to both questions. However, I would bet that these are exceedingly rare cases as even such people will get removed from everyday scientific activities the more they focus on conceptual issues.

I may also add that reading the debates you are having with others here, the disagreements seem to be largely based on trading off the ambiguity of the two separate questions I indicated above. For science to succeed as a practice, it requires no presuppositions about naturalism or anything else. The question is however relevant when thinking about philosophical (epistemological) underpinnings of science, of which naturalism, I would argue is the result of inquiry, not the presupposition of said inquiry. I’ll be curious to see how Massimo handles this issue but presuppositions that would be relevant would be something more akin to the world is a certain way and we can know something about the world, neither of which necessary entails naturalism.

I don’t think that follows, nor do I think it’s true that only philosophers should do such critiques. Philosophy maybe the natural field of inquiry that these questions get raised in but scientists can and have (and ought to!) engage in these questions too. In fact, one of my favorite thinkers, Charles Sanders Peirce, was a practicing scientists who wrote philosophy on the side.

Massimo,

Glad you pointed out Rorty’s departure from the earlier work of Pierce and James.

Susan Haack has severely critiqued his take on Pragmatism and I would definitely agree that his work would be more suited to the “continental” tradition.

LikeLike

Socratic,

Husserl and phenomenology are still big. But this is a book about my views on philosophy, not an encyclopedia…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Coel:

//Many scientists (especially physicists) have a clear scientismistic bent and a strong intuitive sense of the unity of nature and thus of knowledge. //

= and that will be the PR problem of philosophy which you and the others pointed out, including the OP itself, is one of the most pressing issues in philosophy presently. contrary to what you say, i believe it is important that the need of the hour is to emphasize the difference between philosophy and science rather than its similarities. unlike you, i believe the PR problem arises not because philosophers claim their field is different, but because many of them claim it is nothing but part of science itself. and that’s what made the physicist and other scientists wonder: if its part of science, what has it contributed so far? where are its discoveries, its theorems and equations, its laws, its predictions?

its precisely because of people like Quine (not singling him out though) that philosophy suffers from a PR problem. it simply cannot make up its mind about whether its field is different or not – and pretends to be integral to science, while OBVIOUSLY it is not, quinean arguments notwithstanding.

//If a philosopher emphasizes that their field is not science then it can cause the scientist to wonder what it is then? Theology? Post-modernist nonsense? //

= thus the PR problem. we need more popular philosophical works that show what the subject matter is about. one metaphor that captures what the philosophy of science (not the other parts) is about is that it is the “steel-frame of the sciences” (justifications above). it deals with the fundamental presuppositions that the natural sciences take for granted, attempts to work out what’s common between them that we can all label them “science”, attempts to demarcate science from non-science (including from philosophy, theology, and nonsense).

in any case, not just the scientist, even the philosopher wonders what his field is about right from the time pythagoras defined it as the “love of wisdom”, and Plato attempted to differentiate it from the sophists.

//there are important differences between different areas of science such as physics and biology, but no-one really cares about delineating the demarcation. Everyone accepts that they merge seamlessly into each other, and that trying to draw a clear demarcation line would be misguided and silly.//

= though not a sociologist of science, i’m not really sure that it is. but even if it is, well and good! but u miss the point of the comparison. if you wish a better example, it will be this:

– while we cannot tell in any concrete sense the difference between natural and social sciences, it seems pretty obvious that there is (and the demarcation, at least to many philosophers and social scientists, even to natural scientists, is an important one); or another example still

– while we cannot clearly demarcate natural science from mathematics and logic, it seems pretty obvious there is such a difference (and this is a most important philosophical point).

likewise, while it is difficult to differentiate between philosophy and science with in any formulaic manner that you can point to this and always say “this is science” or “nope, that ain’t philosophy!”, it is quite intuitively obvious that there is. just as it is intuitively obvious the arm is not the shoulder, although the line of demarcation maybe blur.

finally, philosophers need to impress on the scientists (improve their PR) that, contra Quine, philosophy is not just philosophy of science. while philosophy of science is indeed important, it is just one part of the whole iceberg, perhaps not even a tenth (figuratively speaking) … although some scientists are aware of this, most seem unaware, and others don’t even care …

LikeLike

//This entire issue shows a certain angst and lack of self-confidence from philosophy as though they’re trying to work out what their place is.//

= i agree completely. when this present generation of philosophers retire and a new one crops up, and more philosophical problems are thrown up by the sciences, the arts and even the new theologies, i hope the confidence will return.

though it is important the angst must always remain, and equally important philosophers should continue engaging in metaphilosophy. as the steel-frame of the sciences (in both the narrow and broad sense), it is important that it remains self-critical and endlessly doubting; after all, we already have the hard sciences to tell us definitive answers, at least within the rubric scientific method …

Regards

LikeLike

Hi Imad Zaheer:

since i completely disagree with virtually everything you write, i shall attempt to be brief.

// if you yet again conflate the question regarding the working of science as it’s done by successful practitioners with the question of epistemological/ontological underpinnings of the enterprise of science. //

= if by the “working of science” you mean the historical, social, cultural and environmental conditions (i can’t see what else you may mean by it), then that is the business of sociologist of science, or perhaps the historians. but not philosophers. yes, there are times when theories here also become philosophical, in which case the history also becomes the philosophy.

my arguments are concerned not directly with the environment of scientific practice, but the nature of the art that they practice – of its epistemology, methodology, its logic, its ontology, and ethics (and all the basic sciences have these). insofar as these are concerned, while the experiences and viewpoints of scientists should not be ignored, these second-order reflections on the nature of scientific practice, is done best by the philosophers of science. that is their calling. that’s their “field” if you wish.

//However, I would bet that these are exceedingly rare cases as even such people will get removed from everyday scientific activities the more they focus on conceptual issues.//

= yes, there are crossover philosophers and scientists. but you may have overstate the need for scientific training to know what the sciences are all about. assuming the scientists have sufficiently portrayed their sciences correctly in their innumerable popularizations (“the selfish gene”, “brief history of time”, etc), i think philosophers can, with a little thought, deduce what their nature is about. and if they happen to get the science wrong when making such deductions, why, there are enough scientists to correct them. in most cases however, philosophers do not get the science wrong. the quarrels are mostly over what to make of the results – namely, of its metaphysical, ethical, methodological, even epistemological implications if any.

//For science to succeed as a practice, it requires no presuppositions about naturalism or anything else.//

= i must completely differ from this. my entire thread is an attempt to argue out how naturalism is the fundamental presupposition of the sciences. and that’s nothing to shy off about. you just simply can’t do science without naturalism, without the presence of natural laws, processes, mechanisms etc. again, you don’t need a scientist to tell you that! its quite obvious really.

if you imagine otherwise, perhaps you can give a hypothetical example of how science can (at least theoretically) be done without the presumption of naturalism; then i will attempt to show you how impossible that is.

//Philosophy maybe the natural field of inquiry that these questions get raised in but scientists can and have (and ought to!) engage in these questions too//

= of course i agree. i have never subscribed to anything less. you seem to have missed my counterfactual here.

i was responding to your argument that “practitioners are the best persons to talk about their subject”. i was arguing against that by saying that IF that is the case, then philosophers are the best persons to talk about philosophy, not scientists, so scientists should stop criticizing philosophy. however, you cannot say “and philosophers should stop talking about science” because, well, ahem, it is the philosopher of science’s field of expertise to talk about science, so as per your proposal, he cannot but talk about it!

i was just trying to draw your argument to its logical conclusion. of course i believe everyone should engage in good philosophy, including scientists, librarians and even politicians … as was the norm only a century back before philosophers since Russell suddenly cooed and retreated from all fronts.

and this is one forum where we are all talking about everything, including science and philosophy. so cheers 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Synred.

Just a short response, then we can continue the conversation again from there.

//To me those methods ARE the scientific method.

What specifically do you mean by scientific method?

Testing hypothesis is what scientist do. Finding out ‘how things works’ is the reason we do it!//

= by the scientific method i mean an algorithm that looks more or less like this:

// step 1: Ask a Question.

step 2: Construct a Hypothesis.

step 3: Test Your Hypothesis by Doing an Experiment or making an observation

step 4: Analyze Your Data and Draw a Conclusion

step 5: Communicate Your Results.

//

and in addition, underpinned by other ideas, of which perhaps the 3 most important are methodological naturalism, uniformitarianism and causation (broadly understood). its simplicity itself, isn’t it?

now all other methods of testing which you have referred to (and which you may subsequently refer) are dependent on this most general method. while those other methods apply within very specific, local domains, this general method underpins them all. in other words, whatever other ‘scientific methods’ you cite, they will always be within the rubric of this general method.

and it is this method you cannot test except on pain of circularity – since in order to test it you have to assume it, then use it. hope that helps a bit.

regards

LikeLike