[for a brief explanation of this ongoing series, as well as a full table of contents, go here]

[for a brief explanation of this ongoing series, as well as a full table of contents, go here]

Yet another challenge: the rise of the Digital Humanities

A very different sort of challenge to the traditional conception of philosophical inquiry comes from the idea of the so-called “Digital Humanities” (DH). This is a complex issue, which includes both administrative pressures on academic departments to “perform” according to easily quantifiable measures and a broader cultural zeitgeist that tends to see value only in activities that are quantitative and look sciency (the broader issue of scientism [3]). I will not comment on either of these aspects here. Instead, I will focus on some basic features of the DH movement (yes, it is another “movement”) and briefly explore its consequences for academic philosophy.

One of the most vocal advocates of DH in philosophy is Peter Bradley, who has expressed his disappointment that too few philosophers attend THATCamp, The Humanities and Technology Camp, which, as its web site explains, “is an open, inexpensive meeting where humanists and technologists of all skill levels learn and build together in sessions proposed on the spot.” [4] This is odd because, as Bradley points out [5], philosophers have been developing digital tools for some time, including the highly successful PhilPapers [6], an increasingly popular database of published and about to be published technical papers and books in philosophy; the associated PhilJobs [7], which is rapidly becoming the main, if not the only, source one needs to find an academic job in philosophy; and a number of others.

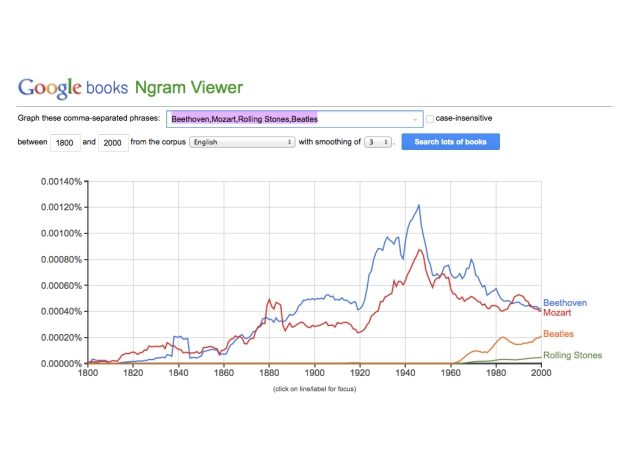

Despite this, philosophers make surprisingly little use of computational tools, such as Google’s Ngram Viewer [8] (more on this below), which Bradley claims is a shame. As an example of its utility, he ran a quick search on the occurrence of the words “Hobbes,” “Locke,” and “Rousseau,” and obtained a diagram clearly showing their “relative importance” from 1900 onwards, as measured by the appearance of these philosophers’ names in books that have been digitized by Google. The result was that Locke and Rousseau have always battled it out while enjoying a significant advantage over Hobbes, and further that Rousseau was ahead of his English rival between the 1920s and ‘50s, but the opposite has been true since the late ‘70s. Now, I don’t know whether scholars of early modern philosophy would agree with such results, but I decided to play with Ngrams myself to get a taste of the approach.

I must say, it is rather addictive, and sometimes really satisfying. For instance, a (non-philosophical) comparison of Beethoven, Mozart, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones led to precisely the outcome I expected: Beethoven and Mozart are between two and ten times more “important” than the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, with Beethoven usually in the lead (except toward the very end of the 20th century), and the Beatles beating the Stones by a comfortable margin (Fig. 6). (Incidentally, Britney Spears barely made an appearance in a 2000-2008 search, and was almost 20 times less popular than Beethoven in 2008 [9]). Of course, it is more than a little debatable whether a popularity context reflected in an indiscriminate collection of books is a better assessment of these philosophers or musicians than the one that comes out of the technical literature in either field. Indeed, I’m not even sure whether the comparison between Ms. Spears and Beethoven is meaningful at all, on musical grounds. Also, as far as the philosophical example produced by Bradley is concerned, shouldn’t we at the least distinguish between the recurrence of certain names in philosophy books, books about politics, and books for a lay audience? It’s hard to imagine that they should all be counted equally, or subsumed into a single broad category. [10]

Despite these reservations, just like the diagrams on the relative influence of philosophers I presented in Chapter 2, this data ought to provide fun food for thought at the least for introductory courses in philosophy (or music), and it may — when done more systematically and in a sufficiently sophisticated manner — present something worth discussing even for professionals in the field. And the data certainly shouldn’t be dismissed just because it is — god forbid! — quantitative. As in the case of XPhi discussed above, the proof is in the pudding, and the burden of evidence at the moment is on the shoulders of supporters of the Digital Humanities. Bradley, for instance, does suggest a number of other applications, such as pulling journal abstracts from the now increasingly available RSS feeds and run searches to identify trends within a given discipline or subfield of study. This actually sounds interesting to me, and I’m looking forward to seeing the results, though one also needs to be mindful that these exercises can all too easily become much more akin to doing sociology of philosophy rather than philosophy itself (exactly the same point made earlier about XPhi).

Lisa Spiro built on Bradley’s points [11], noticing that by 2013 the National Endowment for the Humanities Office of Digital Humanities had awarded only five grants to philosophers at that point (four of them to the same person!), and that the American Philosophical Association meeting that year only featured two sessions on DH, compared to 43 at the American Historical Association and 66 at the Modern Language Association meetings (although, as the author notes, the latter two professional societies are much larger than the APA). Even so, as Spiro herself and several commenters to her article point out, this may be yet another case of philosophers engaging in hyper-criticism of their own discipline (see Chapter 1) while not recognizing their achievements. Besides the already noted PhilPapers, PhilJobs, etc., philosophy can boast one of the very first online open access journals (The Philosopher’s Imprint [12]), the first and only philosophy of biology online open access journal (Philosophy & Theory in Biology [13]), and what I think is by far the best online, freely available, scholarly encyclopedias of any field, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy [14], the quality of whose entries is so high that I regularly use them as either an entry point into a field or topic different from my own or as a quick reminder of where things stand on a given issue. The SEP, incidentally, actually predates Wikipedia!

While a case can be made that philosophers “went digital” before it was cool, and that there is not much reason to think they’ll retreat or disengage any time soon, it is worth broadening the discussion a bit, and ask ourselves what basic arguments in favor and against the whole DH approach have been advanced so far. As in the case of XPhi, the literature is already large, and getting larger by the month. Nonetheless, here is my preliminary attempt at summarizing what some of the defenders and critics of DH have to say at a very general level of discourse.

Just like in any discussion of “the old fashioned ways” vs the “new and exciting path to the future,” there is hype and there is curmudgeonly resistance. An example of the first one — in the allied field of literary criticism — is perhaps an article by Bill Benzon (2014), which begins by boldly stating that “digital criticism is the only game that’s producing anything really new in literary criticism.” It is obvious to retort that new may or may not have anything at all to do with good, however.

The standard example mentioned in this context is the work of Stanford University Franco Moretti, a champion of heavily data-based so-called “distant reading.” The idea, which can easily be transferred to philosophy (though, to my knowledge, has not been, yet) is that instead of focusing on individual books (classical, or “close” reading), one can analyze hundreds or thousands of books at the same time, searching for patterns by using the above mentioned Ngram Viewer or similar, more sophisticated, tools. It seems, however, that this cannot possibly be meant to replace, but rather to complement the classical approach, unless one seriously wants to suggest that we can understand Plato without reading a single one of his dialogues, for instance. Indeed, distant “reading” is really a misnomer, as no reading is actually involved, and the term may lead to unnecessarily confrontational attitudes. The sort of questions one can ask using massive databases is actually significantly different from the “classic” questions of concern to literary critics, philosophers, and other humanists. Some of the times these new questions will indeed nicely complement and integrate the classical approach and address the same concerns from a different standpoint, but in other cases they will simply constitute a change of the subject matter (which is not necessarily a bad thing, but does need to be acknowledged as such).

Data-based techniques can even be applied to single works of literature, as shown by Moretti’s “abstract” reconstruction of the relationships among the characters of Hamlet. The issue is whether a professional literary critic will learn something new from the exercise. Is it surprising, for instance, that Hamlet emerges as the central figure in the diagram (and the play)? Or that he is very closely connected to the Ghost, Horatio, and Claudius, while at the same time relating only indirectly to, say, Reynaldo? I’m no Shakespearean scholar, so I will lead that judgment to the pertinent epistemic community.

Regardless, Benzon makes important points when he places the rise of distant reading in the context of the recent history of literary criticism. To begin with, “reading” in this sense is actually a technical term, referring to explaining the text. And the field has seen a number of more or less radical moves in this respect throughout the second half of the 20th century and beyond. Just think of the so-called New Critics of the post-WWII period, defending the autonomy of the text and the lack of need to know anything about either the author or the cultural milieu in which she wrote the book. And then we have the infamous “French invasion” of American literary criticism, which took place at a crucial 1966 conference on structuralism in Baltimore. Similar considerations have been made concerning the split between analytic and continental philosophy throughout the 20th century, or the rise of postmodernism and the ensuing “science wars” of the 1990s (Chapter 2). Indeed, the parallels between the recent history of philosophy and literary criticism as academic fields are closer than one might expect. Just like philosophers have gone through a “naturalistic turn” (Chapter 3), to the point that many of us nowadays simply wouldn’t even think of ignoring much of what is done in the natural sciences, especially physics, biology and neuroscience, so too a number of literary critics have embraced notions from cognitive science and evolutionary psychology — as problematic as this move sometimes actually is [15].

An entirely different take on the Digital Humanities is the one adopted, for instance, by Adam Kirsch (2014) [16]: at least part of the problem with DH is that the concept seems rather vague. Kirsch points out that plenty of DH conferences, talks and papers are — symptomatically — devoted to that very question (just as, I cannot resist to note, in the parallel case of experimental philosophy). Is DH, then, just a general umbrella for talking about the impact of computer technologies on the practice of the humanities? That seems too vague, and at any rate, philosophy is doing rather well from that perspective, as we have already seen. Or is it more specifically the use of large amounts of data to tackle questions of concern to humanists? In that respect philosophy may indeed be behind, but it isn’t at all clear whether analyses of large data sets on, say, recurrence of words or names in philosophical works is going to be revolutionary (I doubt it), or just one more tool in the toolbox of philosophical inquiry (which seems more sensible).

Kirsch’s criticism is rooted in his reaction to claims by, for instance, the authors of the Digital_Humanities “manifesto” (Burdick et al. 2012): “We live in one of those rare moments of opportunity for the humanities, not unlike other great eras of cultural-historical transformation such as the shift from the scroll to the codex, the invention of movable type, the encounter with the New World, and the Industrial Revolution.” It is rather difficult to refrain from dismissing this sort of grandiosity as hype, which sometimes becomes worrisome, as in the following bit from the same book: “the 8-page essay and the 25-page research paper will have to make room for the game design, the multi-player narrative, the video mash-up, the online exhibit and other new forms and formats as pedagogical exercises.” If by “making room” the authors mean replace, then I’m not at all sure this is something desirable.

And just in case you think this is unrepresentative cherry picking, here is another indicative example uncovered by Kirsch, this time from Erez Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel (2013), the very creators of the Ngram Viewer: “Its consequences will transform how we look at ourselves. … Big data is going to change the humanities [and] transform the social sciences.” And yet, the best example these authors were able to provide to back their claim was a demonstration that the names of certain painters (e.g., Marc Chagall) disappeared from German books during the Nazi period — a phenomenon well known to historians of art and referred to as the case of the “degenerate art” (Peters 2014). Indeed, it is the very fact that this was common knowledge that led Aiden and Michel to run their Ngram search in the first place.

Kirsch also takes on the above mentioned Moretti as a further case in point, and particularly his “Style, Inc.: Reflections on 7,000 Titles” (Moretti 2009). There the author practices data analysis on 7,000 novels published in the UK between 1740 and 1850, looking for patterns. One of the major findings is that during that period book titles evolved from mini-summaries of the subject matter to succinct, reader-enticing short phrases. Which any serious student of British literature would have been able to tell you on the basis of nothing more than her scholarly acquaintance (“close” reading) with that body of work. This does by no means show that DH approaches in general, or even distant reading in particular, are useless, only that the trumpet’s volume ought perhaps to be turned a few notches down, and that DH practitioners need to provide the rest of us with a few convincing examples of truly innovative work leading to new insights, rather than exercises in the elucidation of the obvious.

Here is another example of DH hype, this time specifically about philosophy: Ramsay and Geoffrey Rockwell (2013) write in their “Developing Things: Notes Toward an Epistemology of Building in the Humanities”: “Reading Foucault and applying his theoretical framework can take months or years of application. A web-based text analysis tool could apply its theoretical position in seconds.” As Kirsch drily notes, the issue is to understand what Foucault is saying, which is guaranteed to take far more than seconds, as anyone even superficially familiar with his writings will readily testify.

In general, I think Kirsch hits the nail on the head when he points out that there are limits to quantification, and in particular that a rush to quantify often means that one tends to tackle whatever it is easy to quantify and ignore the rest [17]. But much humanistic, and philosophical, work is inherently qualitative, and simply doesn’t lend itself to statistical summaries such as word counts and number of citations. The latter can be done, of course, but often misses the point. And remarking on this, as Kirsch rightly puts it, is “not Luddism; it is intellectual responsibility.”

Another notable critic of DH is Stephen Marche (2012) who, somewhat predictably at this point, again takes on Moretti’s distant reading approach. Marche does acknowledge that data mining in the context of distant reading is “potentially transformative,” but he suggests that so far at the least this potential has resulted into a shift in attitude more than the production of actually novel insights into literary criticism. He objects to the “distant” modifier in distant reading, claiming that: “Literature cannot meaningfully be treated as data. The problem is essential rather than superficial: literature is not data. Literature is the opposite of data.” Well, not so fast. I don’t see why it can’t be both (and the same goes for philosophy, of course), but I do agree that the burden of evidence rests on those claiming that the old ways of doing things have been shuttered. Then again, critics like Marche virtually shoot themselves in the foot when they go on with this sort of barely sensical statements: “Algorithms are inherently fascistic, because they give the comforting illusion of an alterity to human affairs.” No, algorithms are not inherently fascistic, whatever that means. They are simply procedures that may or may not be relevant to a given task. And that’s where the discussion should squarely be focused.

There are also, thankfully, moderate voices in this debate, for instance that of Ben Merriman (2015), who positively reviewed two of Moretti’s books (together with Joskers’ Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History and Text Analysis with R for Students of Literature). Merriman observes that, at the least at the moment, a lot of work in the Digital Humanities is driven by the availability of new tools, and that the questions themselves remain recognizably humanistic. I don’t think this is a bad idea, and it finds parallels in science: the invention of the electron microscope (or, more recently, of fMRI scanning of the brain), for instance, initially generated a cottage industry of clearly tool-oriented research. But there is no question that electron microscopy (and fMRI scanning) did contribute substantially to the advancement of structural biology (and brain science).

Merriman points out that Moretti and Joskers are more ambitious, explicitly aiming at setting a new agenda for their field, radically altering the kind of questions one asks in humanities scholarship. Some of the examples provided do sound genuinely interesting, if not necessarily earth-shattering: distant reading allow us to study long-term patterns of change and stability in literary genres, for instance, or to arrive at surprisingly simple taxonomies of, say, types of novels (apparently, they all pretty much fall into just six different structural kinds). Some of this work, again, will confirm and expand on what experts in the field already know, in other cases it may provide new insights that in turn will spur new classical scholarship. Merriman refers to the results achieved by DH so far as “mixed,” and that seems to me a fair assessment, but not one on the basis of which we are therefore in a position to dismiss the whole effort as mere scientistic hubris, at the least not yet.

One interesting example of a novel result is Moretti’s claim that he has an explanation for why Conan Doyle’s mystery novels have had such staying power, despite the author having plenty of vigorous competition at the time. The discovery is that mystery novels can be analyzed in terms of how the authors handle the clues to the mystery. Conan Doyle and other successful writers of the genre all have something in common: they make crucial clues consistently visible and available to their readers, thereby drawing them into the narrative as more than just passive recipients of plot twists and turns.

Merriman, however, laments that social scientists and statisticians don’t seem to have taken notice, thus far, of the onset of DH, which is problematic because its current practitioners sometimes mishandle their new tools — for instance giving undue weight to so-called significance values of statistical tests, rather then to the much more informative effect sizes (Henson and Smith 2000; Nakagawa and Cuthill 2007) — a mistake that a more seasoned analyst of quantitative data would not make. It is for this reason, in fact, that one of the books reviewed by Merman is a how-to manual for aspiring DH practitioners. Even so, more cross-disciplinary efforts would likely be beneficial to the whole endeavor, both in literary criticism and in other fields of the humanities, including philosophy.

Speaking of the latter, distant reading is not the only approach that legitimately qualifies as an exercise in the Digital Humanities, and an interesting paper by Goulet (2013) is a good example of the potential value of DH for scholarship in philosophy. The author presents some preliminary analyses of data from a database of ancient Western philosophers, spanning the range from the 6th Century BCE to the 6th Century CE. The survey concerns about 3,000 philosophers, confirming some well known facts, as well as providing us with novel insights into that crucial period of the history of philosophy. For instance, it turns out that about 3.5% of the listed philosophers were women — a small but not insignificant proportion of the total. Interestingly, most of these women were associated with Epicurus’ Garden or with the Stoics of Imperial Rome. Goulet was able to identify a whopping 33 philosophical schools in antiquity, but also to show quantitatively that just four played a dominant role: the Academics-Platonists (20% of total number of philosophers), the Stoics (12%), the Epicureans (8%), and the Aristotelian-Peripatetics (6%), although he notes an additional early peak for the Pythagoreans (13%), whose influence rapidly waned after the 4th Century BCE. Goulet is able to glean a wealth of additional information from the database, information that I would think from now on ought to be part of any serious scholarly discussion of ancient Greco-Roman philosophy.

So, will the DH revolutionize the way we do philosophy? I doubt it. Will they provide additional tools to pursue philosophical scholarship, perhaps together with some versions of XPhi? Very likely. And it is this idea of a set of disciplinary tools and what they can and cannot do that leads us into the next section, where I briefly survey some other instruments in the ever expanding toolbox of philosophical inquiry. The one provided here is not an exhaustive list, and it does not include a treatment of more general approaches that philosophers share with scholars from other fields. But I think it may be useful nonetheless to remind ourselves of and reflect on what the tools of the trade are, in order to complete our analysis of what philosophy is and how it works.

Notes

[3] I have written on scientism in several places, see for instance: Staking positions amongst the varieties of scientism, Scientia Salon, 28 April 2014, accessed on 27 August 2014; Steven Pinker embraces scientism. Bad move, I think, Rationally Speaking, 12 August 2013, accessed on 27 August 2014. I am currently co-editing a book on the topic (together with Maarten Boudry) for the University of Chicago Press.

[4] THATCamp, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[5] See: Where Are the Philosophers? Thoughts from THATCamp Pedagogy, by P. Bradley, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[6] PhilPapers, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[7] PhilJobs, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[8] NGrams, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[9] Although, somewhat disconcertingly, only 20 times less so.

[10] This also raises the question of whether or not the citations are positive or negative, and what that assessment would say about relative importance.

[11] See: Exploring the Significance of Digital Humanities for Philosophy, by Lisa M. Spiro, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[12] The Philosopher’s Imprint, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[13] Philosophy & Theory in Biology, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[14] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on 27 August 2014; The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on 26 August 2015.

[15] I criticize the excessive embracing of evolutionary psychology and other sciences in the humanities here: Who knows what, Aeon Magazine, accessed on 27 August 2014.

[16] You will have noticed that a significant portion of the debate surrounding the DH takes place in the public sphere, not in peer reviewed papers. Welcome to the new academy.

[17] I have often encountered this very same tendency during my practice as an evolutionary biologist, before turning to philosophy full time. It is such a general phenomenon that it has an informal name: the streetlight effect, as in someone looking for his lost keys near the streetlight, regardless of where he actually lost them, because that’s where he can see best.

References

Aiden, E. and Michel, J-P. (2013) Uncharted: Big Data as a Lens on Human Culture. Riverhead Hardcover.

Benzon, B. (2014) The only game in town: digital criticism comes of age. 3quarksdaily, 5 May 2014 (accessed on 27 August 2014).

Burdick, A., Drucker, J., Lunenfeld, P., Presner, T., and Schnapp, A (2012) Digital_Humanities. MIT Press.

Goulet, R. (2013) Ancient philosophers: a first statistical survey. In: M. Chase, S.R.L. Clarke, and M. McGhee (eds.) Philosophy as a Way of Life: Ancients and Moderns — Essays in Honor of Pierre Hadot. John Wiley & Sons.

Henson, R.K. and Smith, A.D. (2000) State of the art in statistical significance and effect size reporting: A review of the APA Task Force report and current trends. Journal of Research & Development in Education 33:285-296.

Kirsch, A (2014) Technology is taking over English departments. New Republic (access on 27 August 2014).

Marche, S. (2012) Literature is not Data: Against Digital Humanities. LA Review of Books (accessed on 27 August 2014).

Merriman, B. (2015) A Science of Literature, Boston Review, 3 August (accessed on 9 May 2016)

Moretti, F. (2009) Style, Inc. Reflections on Seven Thousand Titles (British Novels, 1740–1850), Critical Inquiry 36:134-158.

Nakagawa, S. and Cuthill, I.C. (2007) Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews 82:591–605.

Peters, O. (2014) Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany 1937. Prestel.

Ramsay, S. and Rockwell, G. (2013) “Developing Things: Notes toward an Epistemology of Building in the Digital Humanities,” in: M.K. Gold (ed.), Debates in the Digital Humanities, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 75-84.

Robin, Dennett on free will is a hash extreme, as he has in the past denied being a compatibilist, even. However, since I have staked out the Fourth Peak already, he’s a compatibilist.

LikeLike

To further the aesthetics issue, and Daniel’s previous comment, since he DID mention Ravel (what, no Schnittke, no Penderecki?), there’s the old Latin maxim:

“De Ngramme vidente non disputandum.”

It’s old indeed. Stay maxim-thirsty, my friends.

LikeLike

Hi Robin,

It’s laid out in his latest book “The Big Picture” but II’m 90% sure he also lays it out quite clearly in this video.

He’s claiming physics has eliminated the possibility of any form of LFW leaving only compatibilist versions of FW possible. This is a claim about the naturalist paradigm. Obviously supernatural claims can always be made in the face of any argument from evidence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brodix,

“I find it quite interesting that such an energy consuming function as the mind should have evolved, if its primary function, to make executive level decisions, is irrelevant, since science has determined free will to be an illusion.”

If I’m not mistaken I believe our brain size is primarily due to the need to make the voluminous complex calculations needed for social interaction and cooperation and precisely things like moral reasoning in complex groups.

On FW I don’t think the issue is about what is meant by “free” or “will” but what is meant by “I”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sean Carroll is a compatibilist BTW but as a compatibilist he does not believe in LFW and is claiming as a physicist that it has been ruled out in naturalism.

LikeLike

Supernaturalism and dualism are irrelevant to the free will debate.

In fact most supernaturalist positions are dererministic. Augustine, Aquinas and even Molina all took it for granted that there was only one thing that a given agent would do in a given situation. Islam teaches determinism, as does Calvinism. In fact Libertarian Free Will is very much a minority position among supernaturalists.

And yet the supernatural keeps getting dragged up on this context. I have no idea why.

If it is so clear that LFW is ruled out under Naturalism, ruled out by science, then someone ought to be able to provide a clear technical reason why, using a clear technical definition of LFW.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dan,

# And yes, I do think the problem is that it is entirely quantitative, whereas the question is entirely qualitative. That’s not being curmudgeonly. That’s understanding the difference between the two. #

We part ways there, my friend. I don’t think there is a sharp distinction between qualitative and quantitative questions. To use your example, right, a quantitative comparison of Ravel and EL&P is senseless, and I would hope nobody would do it just because they can. But tracking the influence, as indirectly measured by appearance in books, especially in technical books once the engine becomes more sophisticated, of different musicians may be helpful. I think it pays to be open minded about this one without having to go into the quantitatization frenzy.

Synred,

# Well you need to know about effect size and significance #

Actually, you don’t. I’ve done a bit of research on this when I was running a biology lab. What you do need is effect size and estimates of confidence intervals. P-values simply add an arbitrary, and misleadingly “objective” cut-off point, while a more nuanced inspection of the data aided by effect size and confidence intervals would be more useful but, gasp!, also more subjective…

Coel,

# though it suggests that philosophy doesn’t even aspire to decide between moral realism and anti-realism #

Issue can be settled also by argument, if those in favor of position (a) become overwhelming with comparison to those of position (b). That’s how it is, for instance, in ethics, as well as in political philosophy, so why not metaethics.

As for the weight of empirical evidence, I’ve always said that good philosophy is informed by it, but that empirical evidence tends to underdetermine philosophical questions. If it determines them precisely they cease to be philosophical and become scientific.

Saying that “there is no evidence for moral realism therefore we reject moral realism” is to apply precisely the wrong standard (the scientific one) to a philosophical question.

Garth,

# Amongst all of us here, science has settled that question #

No, philosophy, informed by pertinent empirical evidence, has settled the question for me. (See underdetermination of philosophical issues by scientific evidence above.)

# I can’t put emotions and math into the same category like that. I really don’t think they are analogous #

Perhaps, or perhaps you can’t because the analogy would clearly show where your reasoning goes astray. Ethics and mathematics are not perfectly analogous (but then what is?), but the similarities are sufficient, I think, for my purposes, and simply reject the analogy without argument isn’t helpful.

# Reason as a slave to the passions was not articulated in other words by Plato, Socrates, Aristotle? #

Hum, no.

# I’d call it no more artificial than a beaver damn or a hand axe #

Seriously? Then you may never have seen an iPad. You do know what I’m talking about, right? 😉

Seriously, yes, artificiality comes in degrees, but that doesn’t void the concept. It amazes me how often it comes up in these discussions that because there is no sharp distinction between (a) and (b) therefore people conclude that there are no significant differences between (a) and (b). It just doesn’t follow.

On evopsych, are we now making this into a popularity-among-experts context? Because then I’d like to see quantitative data, and I’m going to bet that the majority of evolutionary biologists, as well as of philosophers of science, are going to be rather skeptical of a lot of evopsych claims.

LikeLike

Hi Robin

I only brought up the supernatural in response to this comment by Massimo to me:

““LFW is untenable within the scientific view that we both share, but of course its defenders will simply say that science does not have access to the sort of reality they are thinking of”

That is why I clarified that Carroll’s claim was a naturalistic one only.

“If it is so clear that LFW is ruled out under Naturalism, ruled out by science, then someone ought to be able to provide a clear technical reason why, using a clear technical definition of LFW.”

I believe Sean Carroll accomplishes this, and Massimo seems to agree, as per his comment above. Plus I’ve never heard a coherent account of any definition of LFW. Again, I’m not claiming this as any ultimate truth, it’s just my opinion, and Sean Carroll’s opinion, and a whole bunch of other scientist’s and philosopher’s opinions. We could all be wrong.

LikeLike

Massimo,

“Perhaps, or perhaps you can’t because the analogy would clearly show where your reasoning goes astray. Ethics and mathematics are not perfectly analogous (but then what is?)”

I honestly see no relation whatsoever. I’m open to you explaining it more to me if you’d care to spend the time, but I also understand if you just can’t be bothered.

Seriously? Then you may never have seen an iPad. You do know what I’m talking about, right?😉

You’ve seen a beaver damn, right? Nature doesn’t do that. Only beavers do that. They can change a whole habitat for hundreds of square miles virtually overnight. Artificial? As I said this is just a semantics preference, not a debate about two different realities. I have no sword to fall on here. Use the term artificial if you like. I don’t find it useful.

“On evopsych, are we now making this into a popularity-among-experts context?”

No. If popularity were important we should all be worshiping the God of Abraham. You pointed to your credentials as a biologist as an explanation for your aversion to EP so I noted other biologists at least as credentialed who advocate for it. So the credential of biologist itself isn’t really an argument or an explanation.

“I’m going to bet that the majority of evolutionary biologists, as well as of philosophers of science, are going to be rather skeptical of a lot of evopsych claims.”

I am skeptical of a lot of evopsych claims. It is an area ripe for abuse by the media, advertising, ideologues, racism, sexism etc. I factor all of that into my credences for it as a field and for each specific claim.

LikeLike

Garth,

Actually I said mind, not brain, as it is the internal, sentient, organizing principle of the brain. As a certain past president said of himself as the executive, “I am the decider.” Which might also go to its often mass generated, basic common denominator primitivism.

Yes, then there is the issue of what is “I” and at what level it is distinct from both the internal and external “we.”

I think the problem of “determinism” is that it is another self aware generated concept that is a form of self measurement and that generates feedback, such that the measurement affects the outcome, as the experiments show.

Though, as I pointed out, I don’t see the combination of “free” and “will” as a particularly useful concept, since it tends to negate the very premise of will, as a distinction/decision making function within the network of environmental factors. Which goes to why it is now associated with libertarianism. Which seems to be about disassociating oneself from contextual inclusiveness.

LikeLike

My main issue being with the overall premise of determinism, as I see time as an effect of action, not the basis for it, such that any action creates feedback and there is no overall linearity. It is more a form of thermodynamic feedback loops, in which causal high pressure is guided by the lower pressure opportunities.

LikeLike

Hi garth,

“Plus I’ve never heard a coherent account of any definition of LFW”

What is incoherent about the definition I gave above? Nothing that I can see.

LikeLike

Hi Massimo,

Though scientific models are also always underdetermined, which is why science uses Occam’s razor routinely.

Anyhow, we both seem to agree that a mixture of conceptual analysis and empirical evidence would be needed to settle moral realism vs anti-realism (though I’m slightly amazed by your “*If* there is a fact of the matter about the issue …”, and your pessimism that the issue can be solved).

But if there is a fact of the matter, then isn’t the scientific standard exactly the right one? By your account, philosophy provides conceptual analysis relevant to the issue, very useful conceptual analysis, but for arriving at conclusions about how the world actually is we use science and empirical evidence.

If I may intrude on your analogy about mathematical Platonism with garthdaisy:

As I see it, mathematical Platonism is an empty concept; it literally has no content. Science can reject empty concepts by shrugging, just as it would if one postulated a new particle that had no properties, no interaction with anything else, and no consequences at all. So, I don’t think your analogy helps you. If moral realism were true (and in any way meaningful) it would have to have some definite content.

Hi Robin,

That’s not how dismissal of bad concepts often works in science. If by dualistic or “libertarian” free will we mean anything that is inconsistent with current known physics, as applied to the brain, then — echoing my comment on the previous thread — the dismissal takes the form: there is no evidence for it; there is no coherent and sensible account of the proposal; there is nothing for which it is needed to explain, and then add in Occam’s razor. It’s thus similar to the way one dismisses elan vital, phlogiston, faeries, gods and unicorns.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Hi Coel,

” If by dualistic or “libertarian” free will .. ”

I just explained why dualism has nothing to do with the case.

Most dualists are determinists.

“we mean anything that is inconsistent with current known physics, as applied to the brain,”

I am currently in the process of asking what that incompatibility is. You appear to be explaining why you don’t have to tell me.

” the dismissal takes the form: there is no evidence for it; there is no coherent and sensible account of the proposal;”

What priposal exactly? Again, part of my question was to find out exactly what proposal you guys are talking about,

So basically you guys are confident that something or other is ruled out by science but you don’t have to explain what that something or other is, or how it is ruled out by science.

Makes sense.

LikeLike

Hi Robin,

As I said, any proposal for “anything that is inconsistent with current known physics, as applied to the brain”. Most conceptions of “libertarian” free will are such. It’s up to proponents of the idea to develop the concept further if they wish to.

Yes, the “something or other” is “anything that is inconsistent with current known physics, as applied to the brain”, and as for “how it is ruled out by science”, see my previous comment.

Indeed.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The conflict is about whether the future is effectively pre-determined and so our present state of consciousness has no bearing on the course of events.

The original premise was that if the location and momentum of all particles were known, then time could be effectively calculated indefinitely, thus pre-determined. The implicit premise though, is there could be an omniscient point of view from which this could be known, rather than points of view being generated internally and subjectively.

The current block time version is that the present is a subjective illusion and all events exist in this omnipresent four dimensional spacetime.

If, on the other had, there is only this present state and the events are being internally generated and as dependent on points of view, as the points of view are dependent on the occurrences of events, then the position that the conscious state, individually, or collectively, that exists in this present state, is not another determining factor, is flawed.

LikeLike

OK

Let me get this clrar.

The claim is made that LFW is ruled out by science.

My question was, “what exactly you meant by LFW and how exactly is it ruled out by science?”

Apparently the answer to my question is that everything that is inconsistent with physics is inconsistent with physics.

And apparently that makes “sense” as an answer to my question

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just watched the Sean Carroll video, very interesting and entertaining, I am always interested in what Carroll has to say, and there is a little overview of QFT which alone makes the video worth watching.

Nothing in it I disagree with, but I can’t see how it answers my question.

LikeLike

Let me try 5o make this a little easier. I agree that if LFW (whatever you mean by it) is inconsistent with physics it is ruled out by science.

So what do you mean by LFW and in what way is it inconsistent with physics?

LikeLiked by 1 person