Panpsychism is in the news. Check out, for instance, this Oxford University Press blog entry by Godehard Brüntrup and Ludwig Jaskolla. Brüntrup is the Erich J. Lejeune Chair at the Munich School of Philosophy, has published a monograph on mental causation, and is the author of a bestselling introduction to the philosophy of mind. Jaskolla, in turn, is a lecturer in philosophy of mind at the same school, his research focusing on the metaphysics and phenomenology of persons, the philosophy of psychology, and the philosophy of action.

Panpsychism is in the news. Check out, for instance, this Oxford University Press blog entry by Godehard Brüntrup and Ludwig Jaskolla. Brüntrup is the Erich J. Lejeune Chair at the Munich School of Philosophy, has published a monograph on mental causation, and is the author of a bestselling introduction to the philosophy of mind. Jaskolla, in turn, is a lecturer in philosophy of mind at the same school, his research focusing on the metaphysics and phenomenology of persons, the philosophy of psychology, and the philosophy of action.

In other words, these are serious people. And so is the paladino-par-excellence of panpsychism, NYU’s David Chalmers. Why, then, are they lending their weight to such a bizarre notion? Let’s talk about it.

The essay begins with a quote by neuroscientist Christof Koch, to the effect that “as a natural scientist, I find a version of panpsychism modified for the 21st century to be the single most elegant and parsimonious explanation for the universe I find myself in.” After which I am compelled to comment that, as a natural scientist myself, panpsychism seems to me both entirely unhelpful and a weird throwback to the (not so good) old times of vitalism in biology.

But according to Brüntrup and Jaskolla, panpsychism is enjoying a Renaissance these days, as attested, among other things, by physicist Henry Stapp’s A Mindful Universe, which embraces a version of the notion strongly reminescent of the thinking of Alfred North Whitehead (the same guy who came up with the quote that gives the name to this blog: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato”).

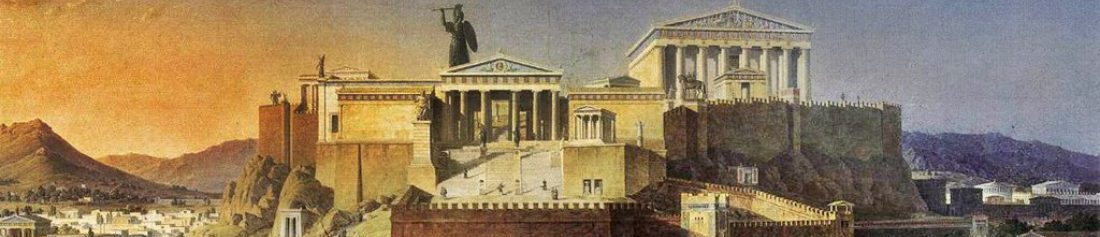

As the OUP authors correctly note, panpsychism is far from being a new notion in philosophy. Before Whitehead, it was endorsed in one form or another by Giordano Bruno, Gottfried Leibniz, and Teilhard de Chardin, and in fact goes back to Thales of Miletus’ claim that “soul is interfused throughout the universe.”

(It was also a crucial notion in Stoic physics, and being myself a practicing Stoic, you would think I would be sympathetic to it. I’m not.)

In 1979, always controversial philosopher Thomas Nagel (also currently at NYU) wrote Mortal Questions, in which he argued that neither “reductive materialism” (as he calls a scientific approach to the study of mind) nor mind-body dualism (obviously) are going to solve the problem of consciousness, which, to him, almost seems like a miracle. Nagel, therefore, saw panpsychism as possibly “the last man standing” on the issue, winning by default, though it isn’t clear why what is essentially an argument from ignorance (science at the moment hasn’t the foggiest about how consciousness emerges when matters organizes in certain ways, therefore science will never know) should carry any weight whatsoever.

(Recall that Nagel was at it again, recently, with a new book criticizing the scientific approach to the understanding of the cosmos as permanently incomplete because it cannot explain either consciousness or morality. The book, Mind and Cosmos, was not favorably reviewed, either by scientists or by philosophers.)

But, as Brüntrup and Jaskolla correctly point out, it is with Chalmers’ 1996 The Conscious Mind that modern panpsychism gets serious, so to speak. And it is therefore time to actually get down to work and see what panpsychism is and why people might be tempted to take the notion seriously.

According to Brüntrup and Jaskolla, “panpsychism is the thesis that mental being is an ubiquitous and fundamental feature pervading the entire universe,” which is an idea that is actually harder to pin down than it sounds. Does that mean that the iPad on which I’m typing this is (partially) conscious? What about the coffee that I just drank as part of my morning intake of caffeine? What about every single atom of air in my office? Every electron? Every string (if they exist)?

The OUP piece goes on to provide a helpful summary of the two cardinal ideas underlying panpsychism. I will quote it verbatim, then we’ll get down to do some unpacking:

“The genetic argument is based on the philosophical principle ‘ex nihilo, nihil fit’ – nothing can bring about something which it does not already possess. If human consciousness came to be through a physical process of evolution, then physical matter must already contain some basic form of mental being. Versions of this argument can be found in both Thomas Nagel’s Mortal Questions (1979) as well as William James’s The Principles of Psychology (1890).”

“The argument from intrinsic natures dates back to Leibniz. More recently it was Sir Bertrand Russell who noted in his Human Knowledge: Its Scope and its Limits (1948): ‘The physical world is only known as regards certain abstract features of its space-time structure – features which, because of their abstractness, do not suffice to show whether the world is, or is not, different in intrinsic character from the world of mind.’ (Russell 1948, 240). Sir Arthur Eddington formulated a very intuitive version of the argument from intrinsic natures in his Space, Time and Gravitation (1920): ‘Physics is the knowledge of structural form, and not knowledge of content. All through the physical world runs that unknown content, which must surely be the stuff of our consciousness.’ (Eddington, 1920, 200).”

Okay, then, let us consider the “genetic argument” first. The “ex nihilo, nihil fit” bit is so bad that it is usually not taken seriously these days outside of theological circles (yes, it is a standard creationist argument!). If we did, then we would not only have no hope of any scientific explanation for consciousness, but also for life (which did come from non-life), for the universe (which did come from non-universe or pre-universe), and indeed for the very laws of nature (where did they come from anyway?).

Then there is a nonsensical bit: “If human consciousness came to be through a physical process of evolution, then physical matter must already contain some basic form of mental being.” To see why this is nonsense, just substitute any qualitatively novel physical or biological phenomenon for “consciousness” and any physical process whatsoever for “evolution” and you’ll see what I mean. The genetic argument, in other words, reduces to an argument from ignorance, or from personal incredulity. It is a non starter from which to build any serious philosophical or scientific position.

On to the second pillar, the “argument from intrinsic nature.”

First off, notice the name dropping and do not be too impressed by it. Just because Leibniz, or Russell (one of my favorite philosophers ever) said something, and even when that something is alost believed by, wait for it, a scientist!, it doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

Second, notice that Russell doesn’t come anywhere near making an argument for panpsychism. At best, that quotation can be interpreted as a statement of agnosticism, and more probably as an example of a philosopher entertaining a notion without necessarily endorsing it (a lot of philosophy is like that).

What about Eddington’s “intuitive” form of the argument? “Physics is the knowledge of structural form, and not knowledge of content. All through the physical world runs that unknown content, which must surely be the stuff of our consciousness.”

Surely. I’m not positive if my physicist friends would agree that physics is the study of structural form but not content — whatever those two terms actually mean in this context. But if so, then this is simply an argument for the incompleteness, as a science, of fundamental physics. Which, of course, is why we have a number of other sciences that study “content,” chiefly — in the case of consciousness — biology.

Consciousness, so far as we know, is an evolved property of certain kinds of animal life forms equipped with a sufficiently complex neural machinery. There is neither evidence nor any reason whatsoever to believe that plants or bacteria are conscious, let alone rocks, individual molecules of water, or atoms.

Moreover, since at the very bottom matter dops not seem to be made of discrete units (there are no “particles,” only wave functions, possibly just one wave function characterizing the entire universe), it simply isn’t clear what it means to say that consciousness is everywhere. Is it a property of the quantum wave function? How? Can we carry out an experiment to test this idea?

One more try. Brüntrup and Jaskolla conclude their piece by quoting Freya Mathews, the author of For the Love of Matter (2003), as presenting an argument that assumes that — somehow — we have privileged access to the ultimate nature of matter by virtue of being conscious. Here is how Mathews puts it: “the materialist view of the world that is a corollary of dualism maroons the epistemic subject in the small if charmed circle of its own subjectivity, and … it is only the reanimation of matter itself that enables the subject to reconnect with reality. This ‘argument from realism’ constitutes my defense of panpsychism.” (Mathews, 2003, 44)

You call this an “argument”? It seems to me to be a massive exercise in begging the question, accompanied by poetic but highly imprecise phrasing (materialism maroons the epistemic subject…). And I simply don’t get why dualism is supposed to be a corollary of the materialist view of the world — I would have thought the two to be incompatible. This isn’t the stuff of either good philosophy or good science.

I am left with just one question: why would anyone take any of this seriously at all? And one possible answer comes right at the end of the OUP post:

“Panpsychism paints a picture of reality that emphasizes a humane and caring relationship with nature due to its fundamental rejection of the Cartesian conception of nature as a mechanism to be exploited by mankind. For the panpsychist, we encounter in nature other entities of intrinsic value, rather than objects to be manipulated for our gain.”

I get it, panpsychism allows us to feel at one with nature because consciousness is everywhere, and that will make us better shepherds of nature itself. I got news: Nature is mind bogglingly bigger than humanity, and it will be here for eons after humanity will be gone. It doesn’t need us to feel connected with her in order to exist. Yes, we do need to take care of our own puny piece of Nature that we call Earth, for our own sake, if nothing else. But we can do that quite independently of either Cartesian dualism or New Age panpsychism. We can do it as material creatures endowed by evolution of the ability to reflect on what they are doing and decide whether it’s a good idea to do it.

(Much more on panpsychism can be found in the corresponding entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, including a third category of arguments, not considered here, and a brief overview of standard counter-arguments.)

So I assume that consciousness is some kind of process allowed by ‘the laws of physics’.

The questions for strong AE are: (1) What is that process?; (2) Can it be emulated on a Turing-like Machine[a]?; (3) Is there something beyond a Turing Machine that could emulate it.

It could be a process that only works for Carbon molecules, but in principle at least the behavior of Carbon can be simulated.

And I note again simulation is not understanding. You could in principle turn the crank of the Standard Model + General Relativity and come out with suns and galaxies. Still w/o higher level concept hydrodynamics and thermodynamics and chemistry you would not understand how it happens.

I don’t know what Searle is trying to get at. Is he aiming at some ‘spirit’ contribution? If so do those ‘spirits’ obey ‘rules of the Spirits” – in which case we would seem to be back where we were and w/o which all hell breaks loose or could.

If the physical world assumption is correct, there is at least one physical process that produces consciousness.

If not a physical world, what? Will and representation of idea, floating free?

[a] Our computers are not full Turing machines. They lack that infinite tape/memory. For most purposes they are close enough.

noun

Philosophy

noun: Vorstellung; plural noun: Vorstellungen

a mental image or idea produced by prior perception of an object, as in memory or imagination, rather than by actual perception.

__________

LikeLike

Bert:

We were only talking about atoms. Atoms are not conscious, bunches of ’em arranged in a brain attached to a body obviously are. More subtle behaviors emerge from group behavior. Physics at the so called fundamental level is not likely to shed any light. Maybe Quantum Mechanics might some how relevant, though all the speculation I’ve seen is pretty much ‘word salad’

I don’t know how conscious arises from stuff. I assume the world is physical and that therefore some kind of physical process produces consciousness. I’m only saying it not single atoms. Maybe there are tiny ghost following the atoms around w/o interfering with them, who aggregate to make minds when the atoms are made into a suitable machine. Sounds like gibberish to me (but also straw).

I see no evidence you understand any physics in your post. You join a few other on my hardly ever read list.

–So long

LikeLike

Massimo,

“I am simply betting that panpsychism will eventually be seen in the way vitalism is seen today.”

I tend to agree. However the definition of “consciousness” is still a work in progress and could get played with down the line if somehow people found a way for it to be useful, in the Wittgenstein sense, to talk about atoms being conscious, or to talk about the entire universe as being conscious. Right now there does’t seem to be any usefulness in talking about consciousness as described by panpsychism.

I do however think it is possible that we may one day in the future find it useful to talk about plants and other lifeforms as being “conscious.” I don’t know how likely this is, but more likely than panpsychism or conscious atoms I would think.

LikeLike

Hi Arthur,

Exactly. So if Searle is right, then consciousness can’t depend on anything like the behaviour of carbon molecules. It would have to depend on something like the physical presence of carbon molecules. Which I personally find absurd.

I don’t think you need to keep noting this, Arthur. I don’t think anybody is confused on this point.

No, certainly not. I guess you’re in luck, in that Massimo’s position is basically identical to Searle’s, so he can explain it to you himself if he has time. Massimo and Searle’s position is called biological naturalism, and as well as rejecting functionalism with the Chinese Room it vehemently rejects any claim that they are appealing to some kind of supernatural element to consciousness. Rather, it is supposed that some as yet undiscovered biological mechanism is at play, such that actual physical neurons can simulate consciousness but simulated neurons cannot. It is supposed that there is a crucial difference between a simulated system and a real system, and a real system is required for consciousness.

I share your intuition that this is not tenable, that it is too arbitrary to suppose that consciousness depends on, e.g. a particular material being present.

LikeLike

I can see consciousness be dependent on the properties of Carbon (as indeed life as we know it is), but if you can simulate those properties you can produce consciousness (at least in a physical world). It might be so hard that we can never do it in practice. We might just have to let it evolve and not have any better idea how it came about than we do now.

Whether true AI can be achieved with something less than such a detailed simulation is an open question. It would be nice as then we’d have some chance of understanding how it comes about.

Any other possibility seems to lead to supernaturalism and I don’t really see how that helps as once we discover the supernatural and presuming it has rules we are back to algorithms anyway.

The only out I see is some kind of idealism where only ‘ideas’ exist and all the stuff is illusion. Seems silly.

I don’t know if everybody understands the simulation is not understanding. Sometimes it seems not. I do harp on it though -{;>(=

LikeLike

Massimo,

I don’t like the term pan-psychism, it seems ready made for abuse, but I do like a mixture of some of the ideas that to fall under it in relation to consciousness and some of the ideas that fall under the ideas of consciousness as emergent, which probably excludes for me the ideas that consciousness as we know it emerges as is, or that consciousness (or mental being) as we know it is ‘ubiquitous and fundamental feature pervading the entire universe’.

“Strong emergentism is much more debatable, and I’m agnostic about it. But notice that people have proposed ways to test empirically if the notion helps or not”

Can you help me find out more on the proposed ways of testing?

LikeLike

“Rather, it is supposed that some as yet undiscovered biological mechanism is at play, such that actual physical neurons can simulate consciousness but simulated neurons cannot. It is supposed that there is a crucial difference between a simulated system and a real system, and a real system is required for consciousness.”

If there was a brain or a system that seemed to be convincing me that it was conscious, I would ascertain whether or not it’s parts are wet or dry. If they are wet I would believe it is conscious. If they are dry I would not believe it was conscious. I call it the old wet/dry test. So far it’s been 100% accurate, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

call it the old wet/dry test. So far it’s been 100% accurate, I think

LOL

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Arthur,

True. I suspect it can, but actually I think whether a conscious AI will ever be feasible is beside the point. I don’t think the question we should be asking is whether we will ever build a conscious AI, but just what sort of thing is consciousness? If it is what it feels like to be a certain kind of information processing system, as I contend, then all we can say is that it ought to be possible in principle.

I’m pessimistic. I think if we ever built a conscious AI, many philosophers would still use the Chinese Room and similar arguments to insist that it’s not actually conscious at all. I don’t think that building such a machine actually gets us anywhere closer to resolving the philosophical issue. Although actual exposure to a conscious AI might tend to leverage our emotions into making us more inclined to accept it a conscious — this would not be for strictly rational reasons. It might eventually be too politically incorrect to dare to suggest that our AI friends are not real people.

I agree but Searle and Massimo would not. Simulated water ain’t wet, etc. Simulated minds ain’t conscious.

LikeLike

DM:

Regardless of the merits of this argument (and as you know, I think it’s misguided) it is not the CR argument. Searle makes an argument of broadly this sort in his 1990 paper “Is the brain a digital computer?”. But it make no mention at all of the CR, and Searle writes: “This is a different argument from the Chinese Room Argument and I should have seen it ten years ago but I did not.”

There’s enough confusion already over the expression “CR argument”, with Searle conflating two different arguments under that heading. Please don’t add a third!

LikeLike

Dan:

I assure you I am perfectly well aware of Searle’s replies, and I’ve addressed them in my post. If you’re referring to his most frequent and more recent reply, concerning syntax and semantics, then the short summary is that it fails to address the Systems Reply at all. It merely switches to a different argument.

It’s certainly your prerogative not to consider the subject again. But I hope you will read my careful refutation, because I’m sad to see you and Massimo endorsing an argument that I consider an embarrassment to philosophy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Richard,

Well, Searle’s response to the systems reply the CR does away with the naive idea that we can simply equate a mind with a physical object. If Searle’s body is both Searle and the CR, then Searle is the CR, and Searle doesn’t understand Chinese. That is why I think you need Platonism to adequately deal with the CR argument, because minds cannot be physical things.

LikeLike

Hi DM,

Wouldn’t it be fairer to say that one part of Searle understands Chinese and another part of him doesn’t? There’s nothing problematic in having two computation machines in the same body, with limited information flow between them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Coel,

It would, but I don’t think you can really argue that these two parts are physically distinct, since they’re both using the same neurons. So the part that identifies as Searle and the part that understands Chinese are not distinct physical entities, and indeed are not physical entities at all. They are just different patterns realised on the same physical stuff. So the mind is a pattern, not a physical thing. So either the mind exists and patterns exist (as on Platonism) or Platonism is false and so the mind doesn’t really exist — we think our minds and our consciousness exists but this is an illusion.

LikeLike

What Thales meant by ‘soul’ infused through the Universe was closer to magnetism than the self-awareness and theory of mind that some animals exhibit (and certainly in that sense, invisible fields do permeate the physical Universe). Modern philosophers cannot be excused for using such wishy-washy words as ‘soul’, at least without detailing which invisible things they mean by it this time.

Interesting comment by garthdaisy, about ‘wet/dry parts’. Maybe expand on it a little and try to define what makes wet wet? How much “liquidness” is needed for consciousness, and could it not also be implemented using flows of other kinds of currents, such as electricity?

LikeLiked by 1 person