I really ought to know better, after decades of activism on behalf of science and critical thinking, than to engage in ideologically loaded discussions with friends or family. Indeed, the opening chapter of the second edition of my Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science from Bunk features two rather frustrating conversations I’ve had with a relative (I call him “Ostinato,” Italian for stubborn) and an acquaintance (“Curiosa,” Italian for curious). Neither episode led to either side moving a fraction of an inch away from their initial position, resulting mostly in aggravation and emotional distress on both sides. Still, as I explain in the book, it wasn’t time entirely wasted, since I came to a couple of important realizations while engaging in such discussions.

I really ought to know better, after decades of activism on behalf of science and critical thinking, than to engage in ideologically loaded discussions with friends or family. Indeed, the opening chapter of the second edition of my Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science from Bunk features two rather frustrating conversations I’ve had with a relative (I call him “Ostinato,” Italian for stubborn) and an acquaintance (“Curiosa,” Italian for curious). Neither episode led to either side moving a fraction of an inch away from their initial position, resulting mostly in aggravation and emotional distress on both sides. Still, as I explain in the book, it wasn’t time entirely wasted, since I came to a couple of important realizations while engaging in such discussions.

For instance, from Ostinato I learned that a common problem in these cases is the confusion between probability and possibility. Whenever I would explain why I don’t think it likely, say, that 9/11 was an insider’s job, or that the Moon landing was a hoax, Ostinato would reply: “but isn’t it possible?” Out of intellectual honesty I would reply, yes, of course it’s possible, in the narrow sense that those scenarios do not entail a logical contradiction. But they are extremely unlikely, and there really aren’t sufficient reasons to take them seriously. Ostinato clearly thought he had scored a major point by wrangling my admission of logical possibility, but such glee reflects a fundamental misunderstanding not just of how science works, but of how commonsense does as well. Is it possible that you will jump from the window and fly rather than crash to the ground? Yes, it is. Would you take the chance?

As for Curiosa, she taught me that a little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing. I nicknamed her that way because she was genuinely curious and intelligent, reading widely about evolution, quantum mechanics, and everything in between. Reading yes, understanding, no. She took any evidence of even extremely marginal disagreement among scientists as, again, evidence that it is possible that what people claim is a well established notion (evolution, climate change) is, in fact, false. Again, yes, it is possible; but no, finding the occasional contrarian scientist (often ideologically motivated, as in the case of anti-evolution biochemist Michael Behe) is absolutely no reason to seriously question an established scientific theory.

You would think that Ostinato and Curiosa had taught me a good lesson, and that I wouldn’t fall for it again. Sure enough, recently a close relative of mine wanted to engage me “as a scientist and a philosopher” in a discussion of chemtrails and 9/11 truthism, sending me a long list of the “reasons” she believed both. I respectfully declined, explaining that my experience had showed me very clearly that nothing good comes out of such discussions. People talk past each other, get upset, and nobody changes his mind. My relative was taken aback by my refusal, but I felt pretty good. Part of Stoic training is the notion that one does not control other people’s opinions, motivations, and reasoning. It is okay to try to teach them, within limits (and I do: that’s why I literally teach courses on this stuff, and write books about it), but failing that, one just has to put up with them.

And yet, Stoicism also reminds me that I ain’t no sage, and that I am labile to slip back at the next occasion. Which I did, a couple of days after Thanksgiving! This time I was having dinner with someone we’ll call Sorprendente (Italian for surprising, the reason for the nickname will become apparent in a moment). She is a very intelligent and highly educated person, who, moreover, is involved in a profession that very much requires critical thinking and intellectual acumen.

Imagine then my astonishment when I discovered that Sorprendente flat out denies the existence of a patriarchy, both historically and in contemporary America. I care enough about this sort of thing that I immediately felt the adrenaline rush to my head, which meant – unfortunately – that I had to fight what I already knew was an impossible battle: to explain certain things to Sorprendente without losing my temper. Anger, as Seneca famously put it, is temporary madness, and should not be indulged under any circumstances. Let alone when you are trying to convince someone you know of a notion that she is adamantly opposed to.

This post isn’t about convincing you that we do live in a patriarchal society. If you don’t think so already there probably is little I can do in a blog post to change your mind. Besides, there are plenty of excellent resources out there (like this one; or this one; or, if you are more practically minded, this one). Rather, I want to reflect on a new (to me) strategy deployed by Sorprendente, a strategy that I didn’t expect in general, and certainly not from someone who very much relies for her job on using the two concepts she dismissed at dinner with me.

Said two concepts are: definitions and facts. When Sorprendente admitted that most positions of powers in our society are held by men I made the comment that that’s part of the definition of a patriarchy. Indeed, here is how the Merriam-Webster puts it:

“Patriarchy (noun). Social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan or family, the legal dependence of wives and children, and the reckoning of descent and inheritance in the male line. Broadly: control by men of a disproportionately large share of power.”

While, thankfully, we are slowly moving away from the first group of markers of a patriarchy (in the West and in some other parts of the world, certainly not everywhere, by a long shot), the second one (the bit after “broadly”) very much applies, even according to Sorprendente herself.

And yet she curtly informed me that “definitions are conversations stoppers.” Wait, what? Definitions of words are, seems to me, crucial to any kind of discourse. Yes, it is true that dictionaries are both descriptive and prescriptive. They are descriptive in the sense that if the common usage of a word changes they will update accordingly; prescriptive because they tell us what currently counts as correct usage. “It’s just semantics” is one of the most irritating responses one can get in the middle of a discussion. Of course semantics (and definitions) are important. If we don’t agree on the meaning of the words we use we are talking past each other, with no possibility whatsoever of understanding. All I was trying to say was that – according to Sorprendente’s own admission – the facts on the ground correspond to the definition of a patriarchy, which means that it becomes inherently contradictory to agree with those facts and yet insist in denying that we live in a patriarchy.

Speaking of facts. Apparently, bringing those up also is a conversation stopper, and it is therefore highly impolite. Here things got truly bizarre. To begin with, it was Sorprendente who brought up a fact, in the form of a statistic: she claimed, as partial evidence that women are not oppressed, that their average life span is 10 years longer than men’s. This is biology, one of my areas of expertise, and the facts can readily be checked.

First off, the 10 years figure is false. The true figure, as it happens, varies from country to country: 6.7 years in the US, a whopping 12 in Russia, and a mere 0.1 in Bangladesh. Second, part of the gap is due to biological reasons: women have two copies of the X chromosome, while men only have one copy (because we have the tiny Y instead). As a result, men are exposed to hundreds more genetically influenced diseases than women, and their mortality is higher, both early in life and throughout. Apparently, however, bringing up these obviously pertinent facts on my part was a rude conversation stopper. Translated: I should be free to bring up whatever false information I want, but you are not allowed to contradict me on the basis of factually correct information. Remember that Sorprendente’s job deals with the accurate verification and interpretation of facts. Oh boy.

Regardless, why would she think that a longer life span is proof that we don’t live in a patriarchy? (Indeed, according to her logic, since women have the statistical advantage, we should conclude that we live in a matriarchal society.) Because women have been and to some extent still are are “shielded” from dangerous jobs, like joining the military, which is an “obvious” example of concern on the part of men. No patriarchy. QED.

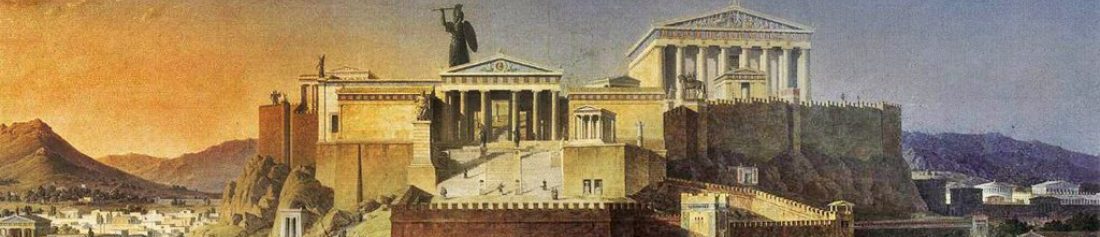

This makes little sense on a number of levels. A military career has always (since the time of the ancient Greeks) be considered a manly job precisely because women have been thought of as inferior or inadequate for that sort of activity. This is exactly what one would expect in a patriarchy. Moreover, it is likely true that most men “care” for women and want to protect them. This is in no way incompatible with the notion of sexism; indeed, being patronizing toward someone who doesn’t actually need to be protected is one of the symptoms of sexism and other discriminatory attitudes. Not to mention that women are now increasingly accepted in the military. This is true both for the US (average life span gap 6.7 years) and Bangladesh (average life span gap 0.1 years). It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that this is simply not a factor in explaining why women live longer than men.

Ah, said Sorprendente, but then if we live in a patriarchal society, how do you explain that there are millions more men than women in prison? This, I tried to respond, actually confuses two different issues, since the majority of men in American prisons are minorities, and particularly blacks and hispanics. The differential is a result of a combination of racism, poverty, and lack of education and therefore job opportunities. It appears, again, to have nothing to do with the issue of patriarchy.

Very clearly, I wasn’t getting anywhere, and both Sorprendente and I were becoming increasingly upset. At which point a thought suddenly struck me and I asked: are you by any chance into Jordan Peterson? Yes, came the response, I think he makes some good points. And that, my friends, was the real conversation stopper.

Time to look back at one of my technical papers, this one published in 2013 with my friend and collaborator Maarten Boudry in the journal Philosophia, and entitled “Prove it! The burden of proof in science vs Pseudoscience disputes.” (As with all my technical papers, they can be downloaded from my DropBox,

Time to look back at one of my technical papers, this one published in 2013 with my friend and collaborator Maarten Boudry in the journal Philosophia, and entitled “Prove it! The burden of proof in science vs Pseudoscience disputes.” (As with all my technical papers, they can be downloaded from my DropBox,

You must be logged in to post a comment.