Panpsychism is in the news. Check out, for instance, this Oxford University Press blog entry by Godehard Brüntrup and Ludwig Jaskolla. Brüntrup is the Erich J. Lejeune Chair at the Munich School of Philosophy, has published a monograph on mental causation, and is the author of a bestselling introduction to the philosophy of mind. Jaskolla, in turn, is a lecturer in philosophy of mind at the same school, his research focusing on the metaphysics and phenomenology of persons, the philosophy of psychology, and the philosophy of action.

Panpsychism is in the news. Check out, for instance, this Oxford University Press blog entry by Godehard Brüntrup and Ludwig Jaskolla. Brüntrup is the Erich J. Lejeune Chair at the Munich School of Philosophy, has published a monograph on mental causation, and is the author of a bestselling introduction to the philosophy of mind. Jaskolla, in turn, is a lecturer in philosophy of mind at the same school, his research focusing on the metaphysics and phenomenology of persons, the philosophy of psychology, and the philosophy of action.

In other words, these are serious people. And so is the paladino-par-excellence of panpsychism, NYU’s David Chalmers. Why, then, are they lending their weight to such a bizarre notion? Let’s talk about it.

The essay begins with a quote by neuroscientist Christof Koch, to the effect that “as a natural scientist, I find a version of panpsychism modified for the 21st century to be the single most elegant and parsimonious explanation for the universe I find myself in.” After which I am compelled to comment that, as a natural scientist myself, panpsychism seems to me both entirely unhelpful and a weird throwback to the (not so good) old times of vitalism in biology.

But according to Brüntrup and Jaskolla, panpsychism is enjoying a Renaissance these days, as attested, among other things, by physicist Henry Stapp’s A Mindful Universe, which embraces a version of the notion strongly reminescent of the thinking of Alfred North Whitehead (the same guy who came up with the quote that gives the name to this blog: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato”).

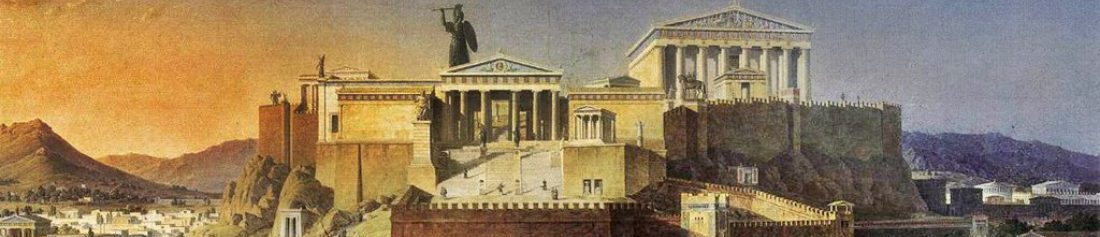

As the OUP authors correctly note, panpsychism is far from being a new notion in philosophy. Before Whitehead, it was endorsed in one form or another by Giordano Bruno, Gottfried Leibniz, and Teilhard de Chardin, and in fact goes back to Thales of Miletus’ claim that “soul is interfused throughout the universe.”

(It was also a crucial notion in Stoic physics, and being myself a practicing Stoic, you would think I would be sympathetic to it. I’m not.)

In 1979, always controversial philosopher Thomas Nagel (also currently at NYU) wrote Mortal Questions, in which he argued that neither “reductive materialism” (as he calls a scientific approach to the study of mind) nor mind-body dualism (obviously) are going to solve the problem of consciousness, which, to him, almost seems like a miracle. Nagel, therefore, saw panpsychism as possibly “the last man standing” on the issue, winning by default, though it isn’t clear why what is essentially an argument from ignorance (science at the moment hasn’t the foggiest about how consciousness emerges when matters organizes in certain ways, therefore science will never know) should carry any weight whatsoever.

(Recall that Nagel was at it again, recently, with a new book criticizing the scientific approach to the understanding of the cosmos as permanently incomplete because it cannot explain either consciousness or morality. The book, Mind and Cosmos, was not favorably reviewed, either by scientists or by philosophers.)

But, as Brüntrup and Jaskolla correctly point out, it is with Chalmers’ 1996 The Conscious Mind that modern panpsychism gets serious, so to speak. And it is therefore time to actually get down to work and see what panpsychism is and why people might be tempted to take the notion seriously.

According to Brüntrup and Jaskolla, “panpsychism is the thesis that mental being is an ubiquitous and fundamental feature pervading the entire universe,” which is an idea that is actually harder to pin down than it sounds. Does that mean that the iPad on which I’m typing this is (partially) conscious? What about the coffee that I just drank as part of my morning intake of caffeine? What about every single atom of air in my office? Every electron? Every string (if they exist)?

The OUP piece goes on to provide a helpful summary of the two cardinal ideas underlying panpsychism. I will quote it verbatim, then we’ll get down to do some unpacking:

“The genetic argument is based on the philosophical principle ‘ex nihilo, nihil fit’ – nothing can bring about something which it does not already possess. If human consciousness came to be through a physical process of evolution, then physical matter must already contain some basic form of mental being. Versions of this argument can be found in both Thomas Nagel’s Mortal Questions (1979) as well as William James’s The Principles of Psychology (1890).”

“The argument from intrinsic natures dates back to Leibniz. More recently it was Sir Bertrand Russell who noted in his Human Knowledge: Its Scope and its Limits (1948): ‘The physical world is only known as regards certain abstract features of its space-time structure – features which, because of their abstractness, do not suffice to show whether the world is, or is not, different in intrinsic character from the world of mind.’ (Russell 1948, 240). Sir Arthur Eddington formulated a very intuitive version of the argument from intrinsic natures in his Space, Time and Gravitation (1920): ‘Physics is the knowledge of structural form, and not knowledge of content. All through the physical world runs that unknown content, which must surely be the stuff of our consciousness.’ (Eddington, 1920, 200).”

Okay, then, let us consider the “genetic argument” first. The “ex nihilo, nihil fit” bit is so bad that it is usually not taken seriously these days outside of theological circles (yes, it is a standard creationist argument!). If we did, then we would not only have no hope of any scientific explanation for consciousness, but also for life (which did come from non-life), for the universe (which did come from non-universe or pre-universe), and indeed for the very laws of nature (where did they come from anyway?).

Then there is a nonsensical bit: “If human consciousness came to be through a physical process of evolution, then physical matter must already contain some basic form of mental being.” To see why this is nonsense, just substitute any qualitatively novel physical or biological phenomenon for “consciousness” and any physical process whatsoever for “evolution” and you’ll see what I mean. The genetic argument, in other words, reduces to an argument from ignorance, or from personal incredulity. It is a non starter from which to build any serious philosophical or scientific position.

On to the second pillar, the “argument from intrinsic nature.”

First off, notice the name dropping and do not be too impressed by it. Just because Leibniz, or Russell (one of my favorite philosophers ever) said something, and even when that something is alost believed by, wait for it, a scientist!, it doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

Second, notice that Russell doesn’t come anywhere near making an argument for panpsychism. At best, that quotation can be interpreted as a statement of agnosticism, and more probably as an example of a philosopher entertaining a notion without necessarily endorsing it (a lot of philosophy is like that).

What about Eddington’s “intuitive” form of the argument? “Physics is the knowledge of structural form, and not knowledge of content. All through the physical world runs that unknown content, which must surely be the stuff of our consciousness.”

Surely. I’m not positive if my physicist friends would agree that physics is the study of structural form but not content — whatever those two terms actually mean in this context. But if so, then this is simply an argument for the incompleteness, as a science, of fundamental physics. Which, of course, is why we have a number of other sciences that study “content,” chiefly — in the case of consciousness — biology.

Consciousness, so far as we know, is an evolved property of certain kinds of animal life forms equipped with a sufficiently complex neural machinery. There is neither evidence nor any reason whatsoever to believe that plants or bacteria are conscious, let alone rocks, individual molecules of water, or atoms.

Moreover, since at the very bottom matter dops not seem to be made of discrete units (there are no “particles,” only wave functions, possibly just one wave function characterizing the entire universe), it simply isn’t clear what it means to say that consciousness is everywhere. Is it a property of the quantum wave function? How? Can we carry out an experiment to test this idea?

One more try. Brüntrup and Jaskolla conclude their piece by quoting Freya Mathews, the author of For the Love of Matter (2003), as presenting an argument that assumes that — somehow — we have privileged access to the ultimate nature of matter by virtue of being conscious. Here is how Mathews puts it: “the materialist view of the world that is a corollary of dualism maroons the epistemic subject in the small if charmed circle of its own subjectivity, and … it is only the reanimation of matter itself that enables the subject to reconnect with reality. This ‘argument from realism’ constitutes my defense of panpsychism.” (Mathews, 2003, 44)

You call this an “argument”? It seems to me to be a massive exercise in begging the question, accompanied by poetic but highly imprecise phrasing (materialism maroons the epistemic subject…). And I simply don’t get why dualism is supposed to be a corollary of the materialist view of the world — I would have thought the two to be incompatible. This isn’t the stuff of either good philosophy or good science.

I am left with just one question: why would anyone take any of this seriously at all? And one possible answer comes right at the end of the OUP post:

“Panpsychism paints a picture of reality that emphasizes a humane and caring relationship with nature due to its fundamental rejection of the Cartesian conception of nature as a mechanism to be exploited by mankind. For the panpsychist, we encounter in nature other entities of intrinsic value, rather than objects to be manipulated for our gain.”

I get it, panpsychism allows us to feel at one with nature because consciousness is everywhere, and that will make us better shepherds of nature itself. I got news: Nature is mind bogglingly bigger than humanity, and it will be here for eons after humanity will be gone. It doesn’t need us to feel connected with her in order to exist. Yes, we do need to take care of our own puny piece of Nature that we call Earth, for our own sake, if nothing else. But we can do that quite independently of either Cartesian dualism or New Age panpsychism. We can do it as material creatures endowed by evolution of the ability to reflect on what they are doing and decide whether it’s a good idea to do it.

(Much more on panpsychism can be found in the corresponding entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, including a third category of arguments, not considered here, and a brief overview of standard counter-arguments.)

I think the argument for the universality of consciousness stems from the fact that in nature no quality or feature of any species is unique to only one species–especially a critical feature.

Also, has anybody any view of Rupert Sheldrake’s “The Science Delusion”?

LikeLike

“Let’s just say you didn’t mean it.”

I am pretty sure I didn’t say it. As I said it doesn’t sound like the sort of thing I say.

“Crap gets into Nature.”

Panpsychism once in Nature Neuroscience may be regarded as a misfortune.

Panpsychism in a number of major scientific journals, publicised by Scientific American and the New York Times and championed by other well known neuroscientists looks like carelessness.

LikeLike

“Just our old friend the brain in the vat in wolves clothing.”

It has nothing whatsoever to do with BIV, completely different point, not even remotely related. If you don’t want to answer my questions just don’t answer them. No reasons required.

LikeLike

Some of you have been kind enough to say that arguing with me is ‘tedious’. But it seems to me that some of you dance around the point a little which might add to that tedium.

LikeLike

John Greenback in https://philosophynow.org/issues/93/The_Science_Delusion_by_Rupert_Sheldrake

LikeLiked by 1 person

Scientific America is now mostly journalist.

In any case science is not immune to BS. Hopefully, it gets sorted out sooner or later.

LikeLike

They are both the same kind unfalsifiable BS. That’s the common thread.

LikeLike

I mean I ask a fairly straightforward question which anyone can either answer or leave – I don’t mind which. But instead I get it compared to some unrelated issue and another question “What difference does it make?”.

The point is that I think that it is pretty certain that we can know that we are not such a computation.

So the point is that the computation would produce language claiming to have conscious states but would not have any such conscious states.

LikeLike

Not every body agrees with your presumption that computation can’t produce consciousness. It is a matter of dispute.

LikeLike

“They are both the same kind unfalsifiable BS. That’s the common thread.”

I am not sure what your criteria for falsifiability are, but I would suggest that we can know with near certainty that we are not such a computation.

LikeLike

Robin: Here you are:

am not sure why you think that the question of why someone else’s consciousness is an unprovable assumption is not an interesting question. here–>Why it should not be something addressed by science.

-Traruh

LikeLike

If what I am experiencing right now is the result of a computation, then, since computation is substrate independent, it could, in principle be being produced by a simple mechanical instantiation of a Turing Machine with a very long tape, being cranked by a little motor. Certainly it would be a long tape and might take billions of years to run just a second or two of consciousness, but it would be in-principle possible.

So I look at the word “the” and seem to see the three letters at once. Even seeming to see the three letters at once would imply a connection.

But if I am the machine described above all of the information involved in those three letters would be spread across a good deal of time and at any given time most of it just sitting there as dots on tape and only one being processed A connection would imply that there is some sort of super process over all those events, that can gather them into a unity. We know of no such super process and, in any case, it would have to be something intelligent which understood the meaning of the symbols with respect to the machine, the symbols having no general meaning in nature.

This seems to make the idea a near impossibility – so I am not a computation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Which is very different to what you claimed I said.

LikeLike

Unfalsifiable:

The BIV can’t tell it’s a BIV. That’s how the problem is defined!

The p-Zombie is defined to be ‘indistinguishable’ (presumably even the p-Zombie would not know its a p-Zombie. If you read out it’s memory with ‘mMRI’ of he future it would record experience of thinking is was conscious, i.e., indistinguishable as stated tin the definition)

Such hypothesis that define away any possibility of falsifying them are … well … unfalsifiable.

God or the Bible is sometimes made unfalsifiable too. After all he could have planted all those fossils, set the carbon dates and created the star light in flight.

However, if that he’s all powerful, all knowing and good, I think has been falsified.

LikeLike

Pretty close. You were asking ‘why it should not be addressed by science?’ I explained why it should not be addressed by science.

If you didn’t want science to address p-zombies why ask ‘why not?’ Anyway that’s how interpreted the question. I took it as a challenge.

LikeLike

Again with the BIV and now you are bringing God into it too. What has She to do with it?

LikeLike

No, not even remotely close.

LikeLike

My own conscious experience is all that I can ever know to exist with perfect certainly. I call this stuff “thought,” or the processing element of the conscious mind. If any of you exist, you could say the same of me and everything that you perceive, and still be certain of your own thought.

By this observation it may seem strange that our only perfect certainty, remains such a weak topic in modern science. Why would consciousness be so steeped in apparent pseudoscientific notions, like panpsychism? Perhaps because associated models and definitions from which to work, have not yet become established. (On that you can check whatever reference you like!) Thus modern ignorance about consciousness, does seem well deserved.

Today I clicked over to SelfAwarePatterns’ website however, and liked what I saw. Mike is in the middle of explaining the position of Todd Feinberg and Jon Mallatt, who’ve developed some models to potentially help. I’m quite pleased with their ambition, as well as his efforts.

While it may be tempting to just accept our situation, and so fight things out using non agreed upon definitions and such, I see no way around our need to develop generally accepted models. Whether personally working on them, or “impartially” assessing the models of others, I see no other way for this magnificent void in human understandings, to become filled.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have explained how they are related (unfalsifiable). You ignore that. I laid it out explicitly for BIV and p-Zombies. You asked how they are related. I answered.

I could come up with other examples. Some versions of God is only one other example. They are not uncommon.

LikeLike

http://existentialcomics.com/comic/67

LikeLike

Yes, I understand that they are other unfalsifiable things that you have thought of, I am just confused as to how an enumeration of unfalsifiable things relates to anything I have said.

If you are saying something is unfalsifiable just say it. Going on to list other unfalsifiable things that you happen to know about does not add anything to that.

As I said before this seems to be dancing round the subject.

LikeLike

This comic is a parody of Philosophy Zombies, an imagined creature that behaves exactly like a human but has no consciousness. David Chalmers (the zombie on the left), believes that even the fact that we can conceive of these zombies means that physicalism (the idea that consciousness, along with everything else, is purely physical) is false. Dan Dennett (the other zombie) believes that the whole thought experiment is incoherent, and that any creature that had the same functionality as humans would simply be conscious.

Philosophers in this comic: Dan Dennett, David Chalmers

Permanent Link to this Comic: http://existentialcomics.com/comic/67

Also, be sure to check out Affect, my wife’s upcoming conference on the work behind social change; in Portland, Oregon

Philosopher Eric commented: “My own conscious experience is all that I can ever know to exist with perfect certainly. I call this stuff “thought,” or the processing element of the conscious mind. If any of you exist, you could say the same of me and everything that you perceive, an”

LikeLike

I did. Several times. What you’re talking about is unfalsifiable.

–>Anyway I’m done…

LikeLike

“Dan Dennett (the other zombie) believes that the whole thought experiment is incoherent, and that any creature that had the same functionality as humans would simply be conscious.”

In other words, Dennett saying that it was falsifiable.

LikeLike

Calling it incoherent is not the same thing as falsifying it. Being incoherent may make it unfalsifiable. I leave that up to the philosophers. Dennett is a philosopher.

“The green slim is red” is incoherent and unfalsifiable. You can’t falsify something that makes no sense. p-zombies don’t seem incoherent to me, but I could be wrong…

Remember it’s only a cartoon. That zombie is not Dennett, but a parody of him. As is, of course, the Chambers zombie.

LikeLike

He said that they would be conscious. So he is saying that the concept is falsifiable and falsified.

Don’t forget that the entire point of the argument is that the concept should be incoherent but that it is not.

The concept is falsified and the argument refuted if the definition can be shown to be incoherent.

Are you saying, as Dennett does, that the concept is incoherent?

And don’t forget, p-zombies were only ever the side track in this.

LikeLike

A parody, yes, but that is Dennett’s position.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Robin,

The fact that there could be computations that claim to be conscious but are not seems to be trivial rather than interesting. I can do it in three lines of code:

start

print “I am conscious”

stop

LikeLiked by 1 person

Robin: Falsifiable refers to whether a statement/hypothesis can be empirically falsified. Incoherent refers to whether the hypothesis is internally consistent. Incoherent statements are unfalsifiable. There’s no inconsistence Coherent statements can be unfalsifiable too. Unfalsifiable statements can even be true, we just can’t know scientifically whether they are true or not because we can’t test ’em.

“The moon is made of green cheese.” It is falsifiable. We’ve sent people and rovers there and know it to be false.

“The moon is as a diameter of the three miles and a radius of 2 light years is incoherent”. It can’t be falsified as it makes no sense. We don’t need to falsify it as it makes no sense.

p-zombies don’t seem incoherent to me, but they are unfalsifiable and thus outside the domain of science. I don’t know what argument Dennett makes that the concept is incoherent. I do feel the idea that merely being able to conceive of them tells us something about how consciousness works or doesn’t is implausible, but I leave that to the philosophers … it is only a cartoon.

Sometimes people say string theory is bad science because it’s unfalsifiable, but it could be that we just don’t know how to falsify it yet. If you can come up with a way to falsify p-zombies have at it, but it seems pretty difficult with ‘indistinguishable’ in the definition.

LikeLike

At the risk of over interpreting the cartoon, it does seem that ‘Zombie Denett’ is referring not to the incoherence of p-zombies as such, but to the further idea that you can deduce something about whether consciousness could be algorithmic or not from our mere ability to conceive of them. That notion seems pretty flaky to me, but I don’t understand it well enough to know.

I’m only saying p-zombies are unfalsifiable and thus unscientific. Chambers might even agree with that, if his argument depends only on being able to conceive of them and not on showing them to exist or not.

LikeLike